You might have seen in the news today that NICE has denied patients access to a ‘pioneering’, ‘breakthrough’, ‘revolutionary’ treatment.

But what actually is this treatment?

CAR-T

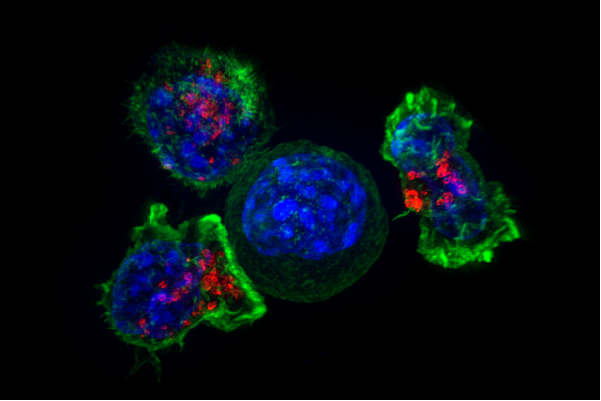

CAR-T therapy is a type of immunotherapy that takes advantage of the cell killing capabilities of cytotoxic T cells. This particular type of T cell is an important part of the human immune system which for many years, researchers have hoped might be useful in treating cancer.

The problem is, cancer cells are derived from your own cells so your immune system has no reason to target them for destruction. That’s where CAR-T therapy comes in. In CAR-T therapy, the T cells of the patient are taken from the blood and genetically modified so they express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). A CAR is basically a signalling molecule on the surface of the T cells that allow them to recognise cancer cells as worthy of destruction. These genetically modified T cells are then put back into the patient’s blood to target and kill cancer cells.

Because we know that different types of cancer typically have different types of signalling molecule on their surface, we can then use different types of CARs to help draw the cell killing T cells to the cancer cells. For example – nearly all types of B cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) have a protein called CD19 on the surface of cells so researchers have been working on CARs that specifically target cells which have CD19 on them.

Yescarta

The specific therapy that NICE has reported on this week is one called Yescarta from a company called Kite Pharma. Yescarta consists of taking T cells from the patient then using a system hijacked from retroviruses to genetically modify the cells. The genetically modified cells are then reintroduced to the patient in a single dose.

Clinical Trials of Yescarta have been initially promising. A phase II single-arm trial found that of 101 patients treated with Yescarta, 54% had a complete response and 52% survived over 18 months. All of these patients had refractory large B-cell lymphoma – that means they had a type of blood cancer that had already failed treatment and the patients had an average expected life expectancy of 3-4 months. While the trial showed that all patients had significant adverse events related to Yescarta, only 3% of patients died from the treatment itself.

Based largely on this trial the FDA approved Yescarta for certain types of lymphoma late last year and the European Commission granted Marketing Authorisation for the treatment this month.

Why not recommend it?

But NICE had some concerns. Firstly, they were concerned that the clinical trials for Yescarta, while promising, were insufficient to allow recommendation of the drug. While this particular type of lymphoma doesn’t have a standard therapy, yet, most patients are treated with scavenger chemotherapy and the Yescarta clinical trials haven’t proven that Yescarta is better than scavenger chemotherapy. The two therapies haven’t been compared side by side. This is quite a significant concern because, without side by side comparison, we can’t be sure that diverting patients from one treatment type to the other is actually beneficial for the health and life expectancy of those patients.

NICE aren’t saying no to Yescarta, they’re saying “not yet”.

The second concern NICE has is that the treatment is currently very expensive. The cost to the UK has not been made available, but in the US the treatment can cost $373,000 per patient. And this is something that NICE has to weigh up in its cost-benefit analysis. So far, Yescarta has been shown to prolong life by approximately 14 months in around 50% of patients. Is it justifiable to divert so many funds to a treatment that only works 50% of the time and we can only say extends life by a year (so far)?

The company that makes Kite Pharma was bought by Gilead Sciences last year, just two months before Yescarta was approved by the FDA. Last year Gilead Sciences had a revenue of $30.4 billion and a free cash flow of $15.9 billion. Gilead Sciences spent $12 billion in order to acquire Kite Pharma and its marketable therapy Yescarta. NICE perhaps has reason to be cautious.

Any other concerns?

If Yescarta were approved for the use in the UK, it would be the first of its type to be approved. There are potential concerns we need to consider when introducing both genetically modified cells into patients and playing around with the immune system in patients. In his article for McGill, Jonathan Jarry pointed out that “Autoimmunity is when our immune system improperly responds to something that belongs to us” and in the case of Yescarta we’re actively training the T cells to recognise cancer cells derived from our own cells. In fact CD19 isn’t just expressed on cancerous B cells, it’s found on all B cells – even the healthy ones. In the case of terminal cancer this might be a price worth paying but it has to be taken into consideration. Sudden activation of T cells in the body is such a strong response that patients can get very sick and even die from a condition called cytotoxic release syndrome.

We must also consider the reproducibility of the initially promising clinical trials. There is evidence that when repeated, less than 50% of clinical trial results are reproducible and many negative clinical trials go entirely unpublished which means a high likelihood of false positives, it seems prudent to take care when making decisions based on single clinical trials.

Conclusion

While many patients were hoping for the approval of Yescarta by NICE, the limitations have proved too high at this stage. I don’t think this decision should be used to criticise NICE or the NHS, rather to encourage further research using reliable controls and a focus on bringing down the prices of promising new treatments. It also highlights an example where the novelty of new treatments can overtake scientific sense and lead to approving treatments which might currently be lacking sufficient clinical evidence supporting their use.

Meanwhile, the NHS will not withdraw funding for any patients already undergoing Yescarta therapy and will reconsider their decision given further research or reduced costs.