A little while ago I wrote about an exciting new potential for HIV treatment. The cool idea was looking to solve a problem we haven’t yet figured out how to solve when it comes to treating HIV infection. You see, HIV is particularly tricky to treat because it forms what we call latent viral reservoirs. These are a group of cells that are infected with the virus but within which the virus isn’t ‘active’.

Antiretroviral drugs are really great, but they only target ‘active’ virus which means these reservoirs are essentially hidden away and protected. This is why people living with HIV need to stay on treatment for their entire lives.

So, researchers came up with a great idea – what if they could ‘kick’ the virus in the reservoirs into action and then ‘kill’ the now active virus using standard therapy. This scientific basis behind this ‘kick and kill’ approach made researchers think that this might hold the key to curing HIV and allowing people living with HIV to eventually come off their medication. Early studies were really promising and there was good evidence that this might be a useful approach to trial in patients.

So what happened next?

RIVER

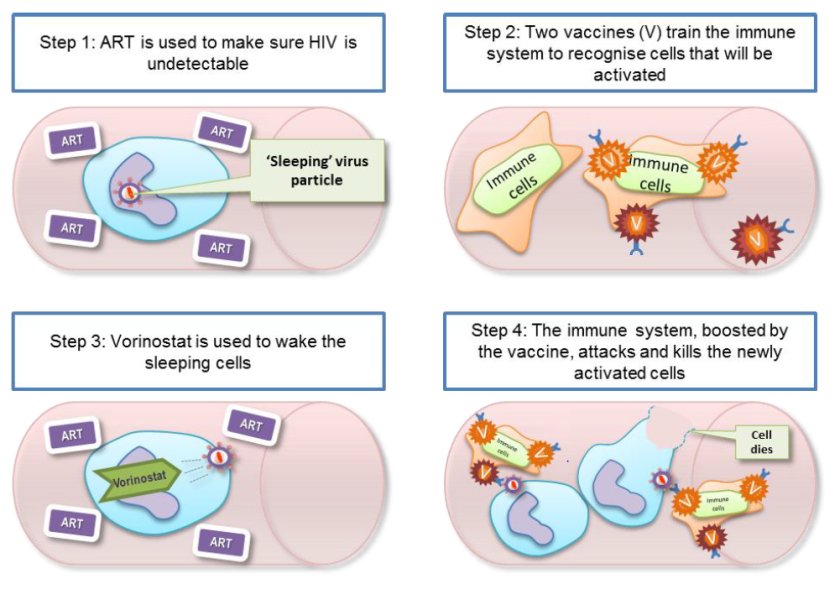

The Research In Viral Eradication of HIV Reservoirs (or RIVER) study began in 2015 and concluded this year. This study was a randomised control trial (RCT) where 60 people recently diagnosed with HIV in trial centres across London and Brighton were split into two groups. One group received standard therapy – antiretroviral therapy (ART) only – this group acted as a ‘control’ group that could be used to compare the test group against. The test group were given a test therapy which consisted of four steps:

- Patients were treated with standard ART until the ‘active’ virus was undetectable in the blood

- Patients were then given a vaccine which would train or ‘prime’ the immune system to recognise the HIV virus

- Patients were treated with Vorinostat which would ‘activate’ the inactive virus in the reservoir cells – this step is the ‘kick’ part of the process

- The ‘primed’ immune system would then be able to ‘kill’ the newly activated virus

What did RIVER find?

The results were surprising and unexpected. RIVER found that there was no significant difference in the size of the latent HIV reservoir between standard treatment (control) and ‘kick and kill’ treated (test) patients. It looked like ‘kick and kill’ was no better than standard therapy.

Even more surprisingly, each of the components –the standard antiretroviral medication, the vaccine which primed the immune cells and the Vorinostat which ‘kicked’ the inactive virus into action – all worked exactly as they should. But combining the multiple components wasn’t any better than ART alone.

Chief Investigator on this study, Prof. Sarah Fidler of Imperial College London said “In the RIVER study, we found that all the separate parts of the kick and kill approach worked as expected and were safe. The vaccine worked on the immune system, the kick drug behaved as we expected it to, and the ART worked in suppressing viral load in the body, but the study has shown that this particular set of treatments together didn’t add up to a potential cure for HIV, based on what we’ve seen so far.”

Does this mean we should drop the kick and kill approach?

Well, no, not really. Because this was just one iteration of the kick and kill approach using a combination of one type of medication and two types of vaccine. Researchers on the RIVER study aren’t really sure why it didn’t work as planned but until we understand the answer to that question it might still be a useful avenue for research.

The co-principal investigator and scientific lead from the University of Oxford, Prof. John Frater says “It is possible that the combinations of drugs we used weren’t quite right, but for this first study we didn’t want to compromise on safety by using stronger agents that might work better but could cause toxicity to the participants. It is possible that vorinostat was not quite potent enough to wake up as much HIV as was needed for the newly trained immune system to recognise. Equally, it is possible that a different sort of immune response to the one we induced is needed to target the HIV reservoir. All of these possibilities need to be teased out and considered to guide our next move in searching for an HIV cure.”

So what next? Collaborative research.

This RCT is an important step in investigating the possibility of curing HIV infection. Professor Abdel Babiker of the MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL, said “Although the results are disappointing, they are unambiguous because of the randomisation and completeness of follow up assessments. Because ART is so effective at reducing viral load, without the randomised control group of participants taking ART alone to compare against, we couldn’t have been so confident in knowing whether the kick and kill drugs had made any impact. It’s important that future HIV cure trials follow this approach and compare their outcomes to an ART-only group.”

Scientific experimentation using RCTs allows us to be confident in the findings – even if those findings are not as promising as we hoped they would be.

This particular trial was part of a UK collaboration group called CHERUB but there are collaborative groups like this all over the world. The value of collaboration allows experts from different backgrounds, with different expertise to come together and conduct research with wide ranges of participants. The importance of participant engagement in particular was praised by Prof. Fidler who said “They are not just volunteers, they are active advocates for support and they push us to go further all the time. They are helping to define where this research can go next and they are the real pioneers of new treatments.”

Find out more about this trial here and here.